Men despite everything. Testimonies from Memorial

Curated by the Russia Cristiana Foundation and Memorial Association

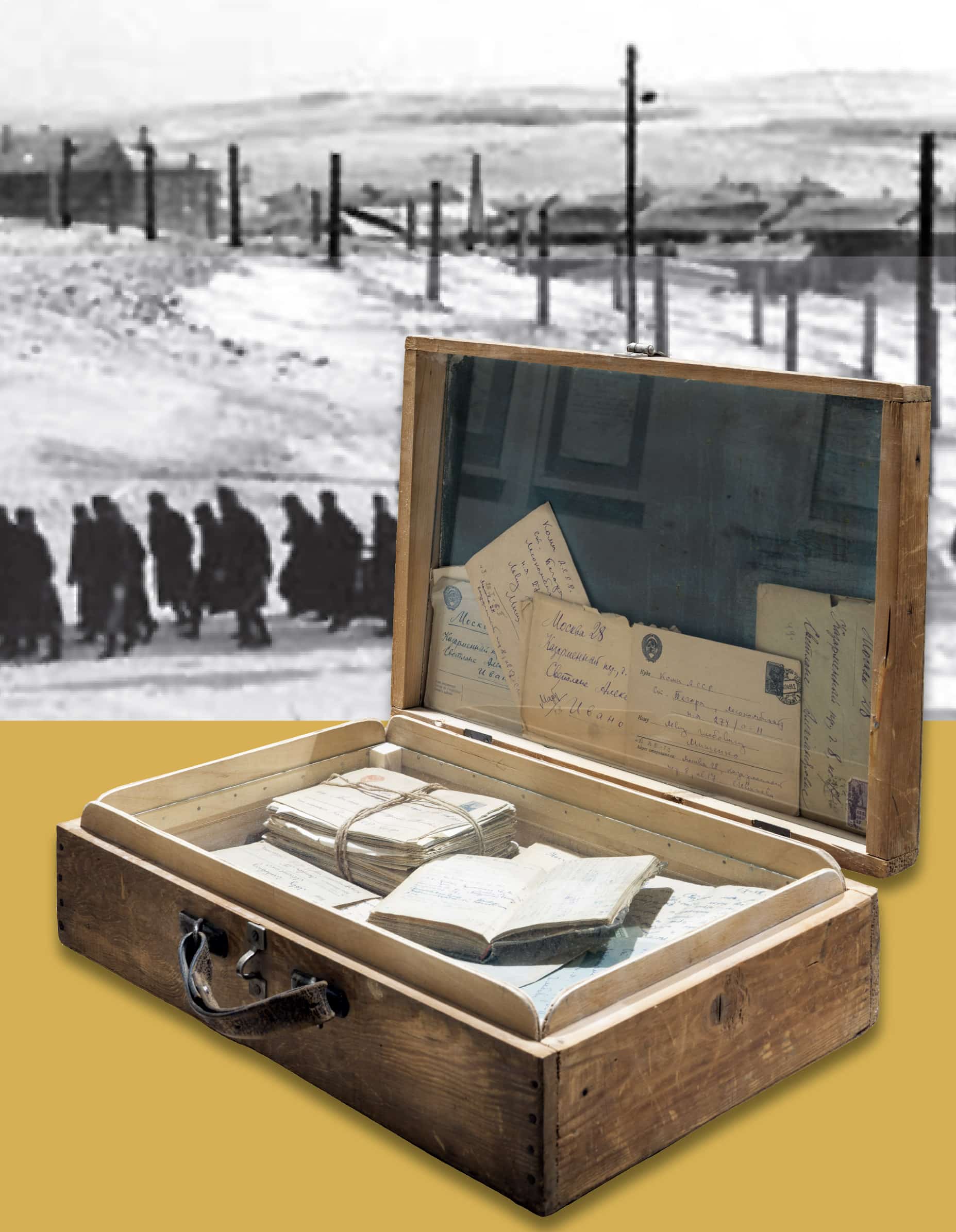

The exhibition is based on two exhibitions held in Moscow in recent years by Memorial based on its own archives and museum collections: the first, dedicated to the letters that fathers wrote to their children and families from the Gulags; the second, on the female universe in these penal colonies, on the small objects (embroideries, drawings, puppets) that imprisoned mothers made for their children in a desperate attempt to keep alive a bond that the passing of years and state propaganda seemed inexorably destined to break.

Through these correspondences and objects – at times poor, naive, at times witnesses of surprising creativity – extraordinary stories of humanity, friendship, pain and truth emerge, documenting the passion for mankind that is preserved in the innermost fibres of each person. Each section alternates between ‘voices’ that emphasise the inhuman conditions, aimed precisely at humiliating and annihilating a person, and others that speak of regained dignity, of a ‘good’ that can shine out everywhere and, despite everything, allow one to remain a man. The exhibition is built on texts, videos and photos (the Memorial collections presented here are currently under sequestration).

Section 1. Memory and Memorial

The first short section is dedicated to Memorial, the first independent public organisation founded in 1989 to preserve the memory of the victims of Soviet repression and liquidated by the Russian authorities in December 2021: its history, its aims, the figures of Andrei Sakharov and Arsenij Roginsky, who were its founders and lynchpins during its 30 years of existence.

Section 2. A message from afar

The theme of memory is inseparable from the possibility of living authentic human relationships.

When faced with the attempt of power to isolate someone, to turn them into a helpless, powerless individual (We are just a number) letters and memoirs jealously guarded, sometimes at great risk. These then testify to the desire not to lose the tremendous but also great experience of humanity lived in the Gulags (Memory: the most precious heritage). This creativity is expressed in messages, prayers, letters, memories transcribed on paper, on pieces of cloth, hidden in clothes, etc.

Writing to go on living: some particularly intense testimonies of how correspondence with loved ones was a way of not falling into despondency or despair.

Section 3. “My loved ones are the star that lights my way…”

The regime wages a fierce struggle against the family (Regime vs. family), because authentic relationships within it are a natural antidote to ideology’s claims to dominate minds. Fathers are arrested and often shot, mothers interned in camps created for the ‘wives of traitors to the fatherland’ (Violated Motherhood). Yet family ties show an extraordinary resilience, under extreme conditions (Guarding Family Ties), to continue to be an educational sphere, a place for the transmission of fundamental values.

Often the regime blackmails children, who have to choose between affection for their parents and faith in the ruling ideology (Whose Fault Is It?). The dilemma of the parents is similarly dramatic, themselves often educated according to revolutionary ideals, who gradually discover the terrible truth of the deception in which they have been brought up, and on the one hand want to help their children to walk a righteous path, while on the other realise that this could mean repression for them (Communist Education).

Section 4. The act of living is not to be renounced

Life within the prison universe in its fundamental aspects:

Work – a curse or freedom

Compassion stronger than ideology

Even the Gulag doesn’t extinguish friendship

Being parents from the Gulag

Thirst for dignity, need for beauty

In particular, the ‘unravelling’ of some stories, the return to freedom after 5, 8, 10 years in the Gulag, shows all the difficulty of returning to life in freedom, of regaining the affection of children, for whom parents often represent strangers, quite different from the people they remember from childhood (Stories with a ‘beautiful ending’). How can one live with the searing wound of lost years, broken lives, and shattered bonds?

Section 5. Mercy or justice?

Everyone in life is called upon to attempt an answer to this question. Here it is the protagonists of the stories narrated in the exhibition who answer it: people who manage not to let themselves be poisoned by resentment, but to ensure that the last word is one of forgiveness and mercy.